A New Discovery by VU Scientists: How Bacterial Argonautes Fight Against Viruses

i

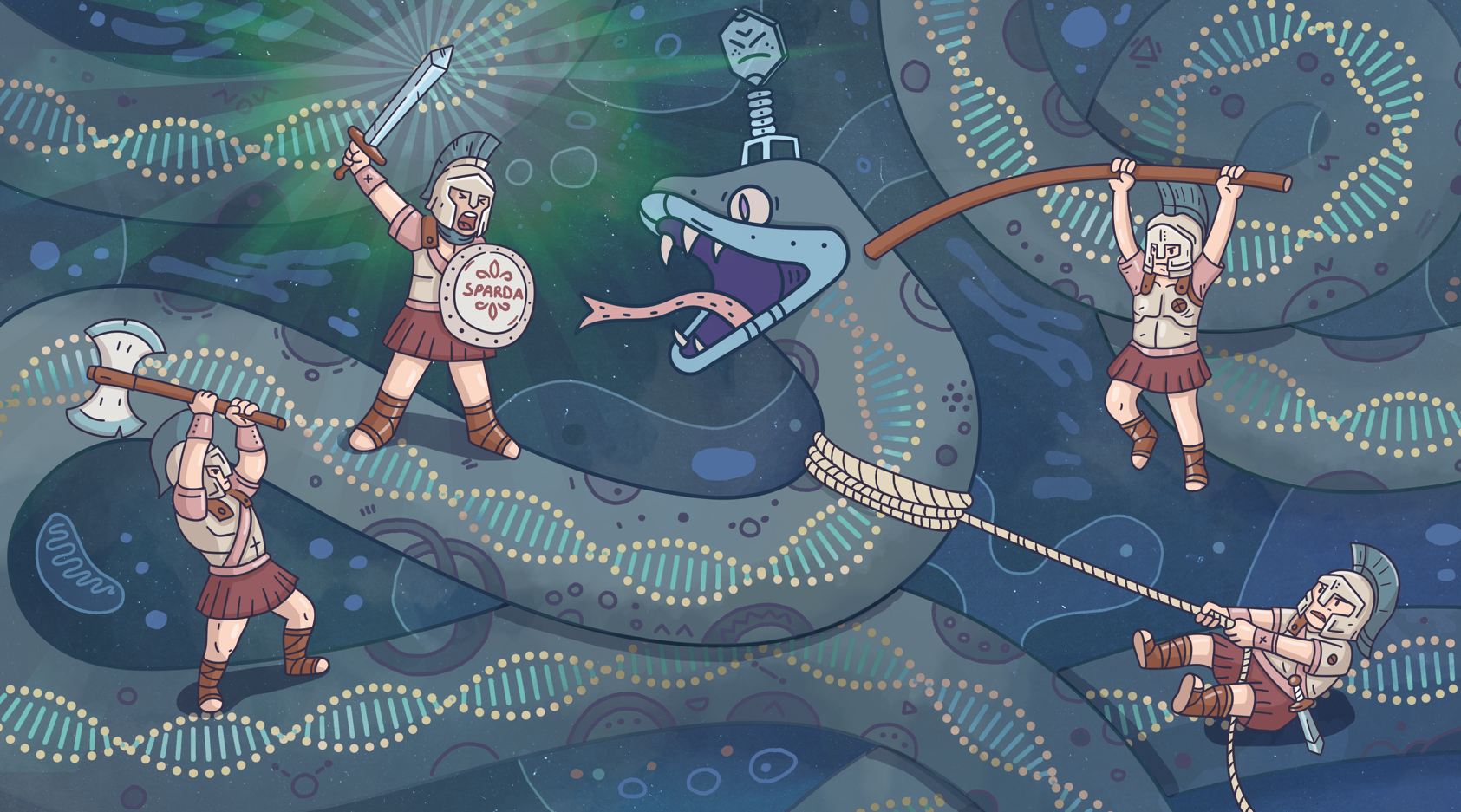

Illustration by Justinas Griciūnas.

In the journal Cell Research of the Nature group, researchers from the Life Sciences Center of Vilnius University published a paper revealing the detailed mechanism of action of the SPARDA (Short Prokaryotic Argonaute, DNase associated) bacterial defence system against viruses. The discovery marks a significant advancement in understanding the bacterial immunity strategies of this type.

According to the research supervisor and Research Professor at the Life Sciences Center of Vilnius University, Dr Mindaugas Zaremba, this research provides a much more accurate understanding of the logic of bacterial immunity – how, after recognising the invader (for example, a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria), structural changes in SPARDA proteins turn into a defensive reaction. Such knowledge is important, both from a fundamental perspective and for the development of new biotechnologies.

The Defence Mechanism Identified

Bacteria and bacteriophages have been involved in a continuous arms race for billions of years. Phages ‘inject’ their genetic material into the cell, take over its resources, multiply, and destroy the bacterial host. During evolution bacteria have developed large number of sophisticated defence mechanisms, and more than two hundred different types of defence systems are currently known. However, only a few are understood, such as restriction-modification systems or CRISPR-Cas, which have become tools for gene engineering and genome editing. Most of the others, including SPARDA, have been little studied so far.

‘SPARDA is interesting in that its activation determines the further fate of the bacterium – it stops the spread of the virus in the bacterial population by sacrificing the host cell itself. To understand this population-level benefit of a self-destructive pathway, we need to uncover the molecular cues and regulatory processes that initiate and control this response,’ noted Dr Zaremba.

According to the biochemist, this research revealed exactly how SPARDA works: from recognising the RNA fragment of the invader (bacteriophage or plasmid) to activating the defence programme. For a long time, this mechanism could only be inferred, but the specific structural changes in the SPARDA protein that caused it were unclear.

Defence-Activating Argonaute Proteins

‘The activation of SPARDA begins with the Argonaute protein. Its name is linked to the Argonauts of Greek mythology – the heroes who accompanied Jason aboard the Argo ship in the quest for the Golden Fleece. True to this reference, Argonaute proteins in the cell ‘search for’ fragments of foreign genetic material: they recognise small pieces of viral RNA inside the bacterium. This is not yet a defence reaction, only a recognised signal that something foreign has been detected in the cell,’ explained the VU researcher.

What happens next was, for a long time, the main secret in the mystery of SPARDA, according to the scientist. However, detailed research has shown exactly how this primary signal turns into a powerful defensive reaction that leads to the death of an infected cell.

‘In the Argonaute protein, we identified a structural region, a beta-relay, which is named due to its similarity to an electrical relay with two states. Beta-relay performs the function of recognising and transmitting the molecular signal. In the absence of a virus infection, the beta-relay is in the inactive ‘OFF’ state. After recognising the virus infection, conformational changes occur in the beta-relay (transition to the active ‘ON’ state), which are transmitted to the surface on the opposite side of the protein. This conformational change allows the protein to interact with other Argonaute proteins that are activated in the same way. Then, the activated proteins begin to assemble into filaments – long, spiral-like structures. Thus, individual activated proteins cooperate by forming a functional megastructure,’ explained Dr Zaremba.

The researcher emphasised that the filamentous form is the active state of SPARDA. In this state, proteins no longer act alone, but as a cooperative complex capable of rapidly and efficiently degrading DNA, which is both the genetic material of the invader (e.g. the virus) and the host (bacteria). Both the host and the invader perish. That is why the reaction of SPARDA is so radical.

‘Another significant revelation in our research is that beta-relay-initiated signal transmission is not limited to SPARDA systems. We detected a similar mechanism in other prokaryotic Argonaute proteins. Therefore, the discovered principle is universal,’ noted Dr Zaremba.

A Self-Sacrificing Strategy for the Benefit of the Population

According to the biochemist, although the SPARDA mechanism seems paradoxical at first glance, evolutionarily, it is a highly effective protection. By activating the defence mode, the system destroys not only the genetic material of the invader – the bacteriophage – but also the DNA of the bacteria itself. An individual bacterium seems to choose to ‘lose the battle’ to win the war – one cell dies, but the virus can no longer spread to the rest of the population.

‘This is a kind of cellular altruism – the death of one cell stops the infection and protects the rest of the community,’ clarified Dr Zaremba. This strategy is not chaotic or random. SPARDA only activates when the Argonaute protein confirms that the cell contains the genetic material of the virus. Only after this very specific signal do proteins begin filament formation and destroy both the virus and host DNA in a coordinated manner. This avoids a false response that would be fatal for an uninfected cell.

This mechanism is part of the ‘abortive infection strategy’ employed by many other defence systems, resulting in the death of the infected host. In the case of SPARDA, the decision to perish is highly and precisely regulated, based on a clear signal sequence at the molecular level. This allows bacteria to achieve a delicate balance between self-preservation and community survival – and that’s what SPARDA does in a manner interesting in terms of both fundamental biology and the development of new biotechnologies.

A Driving Force: The Potential for Application

‘The research on bacterial protection systems is developing extremely rapidly, so we felt part of the global race while working on this research. Here, every revealed mechanism is important – both for science and when applied in practical innovations,’ said Dr Zaremba.

In the food industry, this knowledge allows the bacteria used for fermentation to be protected from phage attacks, which can lead to the preservation of the whole batch of cheese or yoghurt. In biotechnology, SPARDA can be used to develop precise nucleic acid detection tools, as this system accurately recognises the virus.

In medicine, where the antibiotic resistance of bacteria is rapidly increasing, there is a growing focus on phage therapy, an alternative approach that can help treat complex infections. For such therapies to be effective, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms that bacteria employ to defend themselves against viruses. The discovery of how SPARDA operates enables scientists to better predict which bacteria can be resistant to phages and assists in the development of more tailored therapeutic strategies.

‘If we want to develop bacteriophages for therapy, we need to understand what defence mechanisms bacteria use. In other words, without knowing the arsenal of enemies, we cannot prepare an effective defence plan,’ concluded the researcher.

The Team That Solved the SPARDA Puzzle

Research into SPARDA was carried out by a large team of researchers at the Life Sciences Center of Vilnius University with different competencies: bioinformatics Prof. Česlovas Venclovas, PhD student Simonas Ašmontas, Algirdas Grybauskas; biochemists Dr Evelina Zagorskaitė, Dr Paulius Toliušis, Dr Arūnas Šilanskas, PhD student Edvinas Jurgelaitis, PhD student Ugnė Tylenytė; immunologist Indrė Dalgėdienė; Dr Elena Manakova, who conducted structural studies, and Dr Marijonas Tutkus and PhD student Aurimas Kopūstas, who conducted single-molecule experiments.

Research supervisor Dr Zaremba revealed that to understand this arsenal, a comprehensive methodological approach was required. ‘Bioinformatics experts used an unusual out-of-the-box protein structures’ analysis to identify the structural region of the beta-relay. Biochemists researched how these proteins recognise viral targets and activate themselves. The methods used to study individual molecules allowed us to observe the SPARDA filament formation in real time, while X-ray crystallography and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provided an accurate structural image of the SPARDA protein at the atomic level – what exactly the protein looks like in a inactive state and when its defence mode is activated,’ explained Dr Zaremba.

The research was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) (S-MIP-24-40, S-MIP-24-58, S-MIP-23-131), Horizon Europe HORIZON-MSCA-2021-SE-01 project FLORIN (101086142), CPVA (01.2.2-CPVA-V-716-01-0001), iNEXT (653706), and the Vilnius University Research Promotion Fund (MSF-JM-20/2023, MSF-JM-05/2024).