"Plica Polonica" Through Centuries: the Most “Horrible, Incurable, & Unsightly” Or a Personal Hygiene Problem?

For millennia, some diseases of the humankind have been treated as God's punishment for sins or even the manifestation of "evil spirits." Some physicians of the nineteenth century, famous for their remarkable advances in the science of medicine, had also come a long way in finding the true origin of diseases. Eglė Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė, a physician at the Centre for Neurology in Vilnius University (VU) Hospital Santaros clinics; a lecturer at the Institute of Health Sciences in the VU Faculty of Medicine, wrote an article on plica polonica – a condition which was a result of dirt, uncombed and filthy hair plaits in hairy parts of the body, but long considered to be a multi-organ and devastating disease.

For millennia, some diseases of the humankind have been treated as God's punishment for sins or even the manifestation of "evil spirits." Some physicians of the nineteenth century, famous for their remarkable advances in the science of medicine, had also come a long way in finding the true origin of diseases. Eglė Sakalauskaitė-Juodeikienė, a physician at the Centre for Neurology in Vilnius University (VU) Hospital Santaros clinics; a lecturer at the Institute of Health Sciences in the VU Faculty of Medicine, wrote an article on plica polonica – a condition which was a result of dirt, uncombed and filthy hair plaits in hairy parts of the body, but long considered to be a multi-organ and devastating disease.

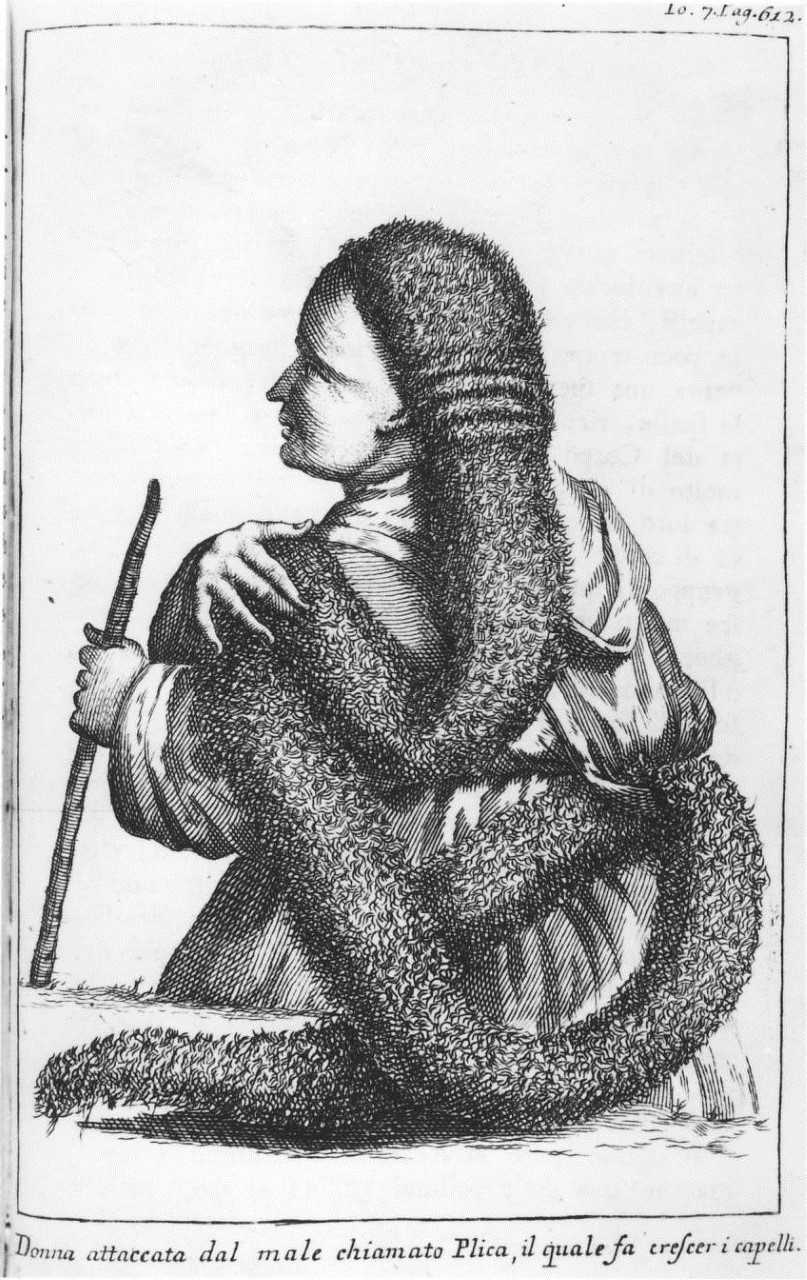

Plica polonica has also been called plica polonica judaica, trichoma, lues sarmatica in Latin, kołtki, goźdźiec, kołtun in Polish, kaltūnas in Lithuanian, la plique polonaise in French, and weichselzopf, judenzopf, or hexenzopf in German. Its signs and symptoms, as it was commonly believed, included irreversible plaiting of the hair accompanied by lice, headaches, mutilating arthritis, scoliosis, and onychogryphosis.

Approximately 900 articles have been published on plica polonica up to the 19th century. Early on, the regional disorder had been thought to be caused by a witch's spell or a supernatural influence that some people related to a punishment from God. As such, it could not be removed simply by cutting off a patient's hair. In fact, it was widely believed that this could result in serious complications, even the patient’s death. It was also believed that the disorder could lead to ulcerations, apoplexy, seizures, headaches, insomnia, blindness, deafness, and a myriad of other aches and diseases. This was because the disease or its agent was thought to circulate in the blood, and could spread systemically throughout the body. Characterized by a tuft of matted, felted, and filthy hair, plica polonica was then considered an affliction affecting predominantly people living in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Stephanus Bisius (1724 – 1790), a professor of VU, in his Responsum Stephani Bisii Philosophiae et Medicinae Doctoris ad Amicum Philosophum De Melancholia, Mania et Plica Polonica sciscitantem, published in Vilnius in 1772, criticized all attempts to associate medicine with metaphysical speculations. Bisius told the readers that plica polonica is not a real disease. The symptoms, which are often attributed to plica, are related to other diseases, such as scurvy, venereal diseases and other. Plica polonica is only the result of superstitions circulating among people lacking knowledge about its causes. Diseases with unknown causes, he wrote, are often wrongly interpreted and attributed. If plica polonica were a real disease, it should have unique diagnostic and pathognomonic symptoms, which it lacks. Therefore, “plica is not a disease, but a human error, derived from their negligence and superstitions, nourished by old women’s deceit and obscurity, strengthened by the unreasonable credulity of priests,” he concluded.

Surprisingly, what Bisius wrote, generated a more severe negative reaction from his medical colleagues than from clergy. For example, Joseph Frank (1771 – 1842), the highly-respected physician who lived and worked in Vilnius in the early-19th century, mentioned in his Mémoires that plica polonica should be considered as “a national plague, a result of chronic contagions and local conditions ... disastrous for the current population“, adding that "it will harm future generations”. Unlike Bisius, he strictly forbade cutting off the affected hair. Remarkably, plica polonica was believed to be a multi–organ disease until the end of the 19th century in Vilnius and other Western and Eastern European cities.