Under One Sky: A Spanish Astrophysicist’s Life and Work in Lithuania

After more than 15 years spent studying and working across Europe and Latin America, Spanish astrophysicist Dr Carlos Viscasillas Vázquez has found an unexpected but lasting home at Vilnius University (VU). Now based at the Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy, he conducts cutting-edge research on stellar evolution and leads international science outreach initiatives. From decoding the Milky Way to organising Baltic-wide exhibitions, Dr Viscasillas is contributing to Lithuania’s growing visibility in global astronomy, and says he’s proud to call Vilnius his academic and personal home.

When did you first relocate to Lithuania, and what were the personal and professional factors that influenced your decision?

Before settling permanently in Lithuania, I had several stays here. In 2009, I took an intensive Lithuanian language course at LCC International University in Klaipėda, which that summer left a lasting impression.

I returned through EU programmes such as Comenius and Grundtvig – first in 2010 as an assistant teacher at Atgimimas School in Druskininkai and again in 2011–2012 at Žemaitijos kolegija in Rietavas, complemented by short stays at the Druskininkų švietimo centras, the Žemaitijos kolegija in Telšiai and the University of Klaipėda. Each of these experiences deepened my connection with the country.

In 2013, during an internship at Molėtai Astronomical Observatory, I was fascinated by the work and environment there. My mentor at the time, Rimvydas Janulis, inspired my career path. After working briefly in the private sector, I came back to start my PhD – marking the moment I truly made Lithuania my home.

Today, Lithuania is not only where I work and do research, but also where I’ve built a beautiful family and a life, I’m very proud of.

Could you tell us a bit about your current research focus?

My research spans a variety of topics, but is primarily focused on the chemical and dynamical evolution of our Galaxy, studied through its stars and star clusters. For instance, very recently, we utilised stellar chemical abundances to chart the spiral arms of the Milky Way’s inner disc – the first time this has been accomplished in such a manner.

In another recent work, we’ve also made significant progress in understanding the dynamical evolution of open clusters with unprecedented precision. Beyond my core research, I’m also passionate about advanced techniques and data-driven approaches in astronomy.

Being among the most data-intensive sciences, astronomy demands both innovative tools and new ways of thinking. I also enjoy observational work at our beautiful VU Observatory in Molėtai, where the wonder of the night sky and the beauty of nature meet the rigour of modern astrophysics.

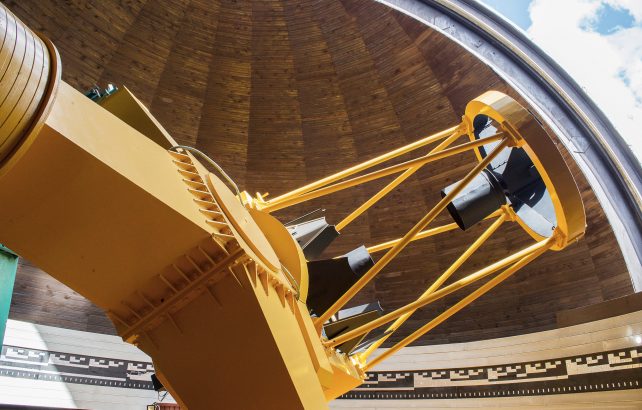

The 1.65 m telescope of the Molėtai Astronomical Observatory, Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy, Faculty of Physics, Vilnius University. Photo by A. Zigmantas.

The 1.65 m telescope of the Molėtai Astronomical Observatory, Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy, Faculty of Physics, Vilnius University. Photo by A. Zigmantas.

The Astrospectroscopy and Exoplanets Group, led by Professor Gražina Tautvaišienė, stands out as one of the most internationally diverse scientific teams – not only within the Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy but across the entire Faculty of Physics. Could you share your impressions of the international atmosphere, especially through the collaborative networks you’ve been building?

I truly believe that astronomy is one of the most international sciences. In that sense, I find the International Astronomical Union’s centenary motto from 2019, “Under One Sky,” very meaningful – it reminds us that, from above, there are no borders separating countries. At our institute, this spirit of internationality is very much alive. In the Astrospectroscopy and Exoplanets Group, where I work, with almost half of my colleagues coming from different parts of the world – Ukraine, Austria, India, Croatia, Spain, and Lithuania – we create a truly global and collaborative environment.

This strong international atmosphere also mirrors the vision of Gražina Tautvaišienė, who currently serves as Vice-President of the International Astronomical Union, an organisation that brings together nearly 13,000 individual members from around 90 countries. International experiences are one of the most rewarding aspects of a research career.

Personally, I have built two strong and lasting collaborations with institutions in Spain and Italy, working closely with two outstanding researchers: Laura Magrini from the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory and Ana Ulla from the University of Vigo. In recognition of this collaboration, I was honoured to be appointed as an associate researcher at INAF-Arcetri last year, something that means a great deal to me. Maintaining these strong ties with southern Europe not only keeps me connected to my roots but also helps build bridges between our university and research centres abroad.

Throughout my journey, I have had the privilege of meeting many exceptional scientists. The warmth, generosity, and openness of the astronomical community in Europe and around the world have been key to building strong cooperation networks – and have made the path all the more fulfilling.

Can you tell us more about the initiative to unite Spanish researchers working in the Baltic States, and how it fosters interdisciplinary collaboration across different scientific fields?

Last year, a group of Spanish scientists in the Baltic founded the association ACEBaltic, during a vibrant gathering at the Academy of Sciences in Tallinn, joined by inspiring colleagues, including prof. Gražina Tautvaišienė, and the Chairman of the Research Council of Lithuania, Gintaras Valinčius, Ambassadors and representatives from the Research Councils of the three Baltic countries and Spain.

ACEBaltic is now part of RAICEX, the global network of Spanish researchers abroad, which connects nearly 5,000 scientists around the world. These networks are incredibly valuable – not only for creating a sense of community, but also for encouraging interdisciplinary dialogue.

In March, we organised a scientific road trip across the Baltic States, visiting six astronomical observatories and bringing together scientists from Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Spain. It was a great opportunity to share ideas, build new collaborations, and strengthen ties between our scientific communities in a relaxed and inspiring setting.

Last year, I also had the opportunity to attend the 10th anniversary of ACES, the Association of Spanish Scientists in Sweden, in Stockholm. There I met neurologists, biologists, and experts from many other fields. These associations allow us to share knowledge, collaborate across disciplines, and support each other.

Congratulations on receiving support from the VU Research Promotion Fund this year for your project “Unveiling the Nature of Hot Subdwarfs through Spectroscopy and Machine Learning”. Could you share a bit more about this research?

Our project explores one of the big unanswered questions in stellar astrophysics: the origin and evolution of hot subdwarf stars. These stars are thought to form mainly in binary systems, because they lose their hydrogen envelope at some point in their stellar evolution, but we still don’t fully understand how this process works.

Thanks to the Gaia spacecraft, we now have access to spectra of a large sample of hot subdwarf candidates and will apply advanced AI techniques to analyse this complex dataset. We’ll also observe selected stars using the high-resolution Vilnius University Echelle Spectrograph (VUES) at our Observatory in Molėtai.

This project will allow us to maximise the capabilities and potential of VUES with this new research line. I’m also fortunate to work with a fantastic team: one of my talented master’s students, Vladas Šatas, and Aidas Medžiūnas, an expert from the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics and enthusiastic about these sciences applied to astrophysics. My VU colleague, astrophysicist Dr Markus Ambrosch (originally from Austria), brings deep expertise in applying machine learning techniques to astronomy and spectroscopy.

Together, we form an international, multidisciplinary team. This project stems from my regular research visits to the University of Vigo, thanks to close collaboration with Professor Ana Ulla Miguel, a renowned expert in hot subdwarfs whose long-standing work has greatly influenced this initiative.

You’re clearly committed to popularising science through teaching and outreach – regularly visiting schools and organising various events. Is this a consistent part of your work, and what motivates you to remain so actively involved?

I believe scientists should devote a small part of their time to outreach for several important reasons. First, it’s a way to give back to society for its investment in science. Second, it helps nurture future generations of astronomers.

In today’s world of information overload, it’s more important than ever to educate the public about science. With this in mind, I work alongside my colleague Dr Šarūnas Mikolaitis on various outreach initiatives in Lithuania, through the International Astronomical Union (IAU), its Office for Astronomy Outreach (OAO) and the Network for Astronomy School Education (NASE), as well as the European Association for Astronomy Education (EAAE).

At the Tõravere Observatory of the University of Tartu. Photo by Viljo Allik.

At the Tõravere Observatory of the University of Tartu. Photo by Viljo Allik.

We’ve partnered with institutions such as the Spanish Embassy to deliver three annual exhibitions: AstrónomAs (2023), A Universe of Light (2024), and A Billion Eyes for a Billion Stars (2025). These touring exhibitions have reached thousands across Lithuania, particularly young people. Alongside these initiatives, we’ve welcomed leading scientific figures to the country, including ESA astronaut Sara García (2023), ESO Director General Xavier Barcons (2024), and this year we plan to welcome NASA engineer Begoña Vila, who works on the James Webb Space Telescope and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. We’re confident that these efforts will inspire new scientific vocations in the coming years.

How many countries have you lived, studied, or worked in, and in what ways have those international experiences shaped your personal or professional journey?

I’ve been living abroad for 15 years. It helped me grow personally, discovering new parts of myself. Funny thing, I’ve never experienced a country in the way tourists would.

Before beginning my PhD at VU, I had the privilege of undertaking internships at several institutions that deeply shaped my path. These included the VU Molėtai Astronomical Observatory in 2013, the Center for Astroengineering (AIUC) in Chile in 2014, the Seismological Station in Thessaloniki, Greece, in 2015, and the European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) of the European Space Agency (ESA) in 2017. Each experience not only strengthened my passion for astronomy and science but also played a pivotal role in my decision to commit my life to astrophysics.

Programs like Erasmus have opened countless doors – not only promoting student exchange but also supporting teaching and collaboration across Europe. My first Erasmus experience was in 2007, at the “Angel Kanchev” University of Ruse in Bulgaria. It’s truly encouraging to see how Erasmus has expanded to support researchers and educators at different stages of their careers.

Thanks to various European and international programmes, I’ve studied or taught in Mexico, Chile, Greece, Sweden, and now Lithuania, where I’ve built both a career and a family. These experiences have shaped my identity and values, and I’m excited to continue this journey with an upcoming Erasmus+ exchange involving the National University of Equatorial Guinea and Vilnius University.

International experience is vital for scientific progress – collaborating globally enriches research and benefits society as a whole.

Do you find the Lithuanian language particularly challenging, and would you encourage other scientists to consider moving to Lithuania to live and work?

Switching languages has always come naturally to me, growing up in Galicia with both Galician and Spanish. I’ve always believed that learning the local language is key to integration, and Lithuania was no exception.

Although I attended two intensive Lithuanian courses, I learned the most through everyday life. In Rietavas, I began using the language daily, even picking up some Samogitian dialect. I now speak Lithuanian at work and at home, including with my Ukrainian colleague Dr Yuriy Chorniy. We’ve spoken only Lithuanian for years since we share no other common language. Lithuanian is a beautiful, intellectually rich language with ancient roots.

I’m proud to work at Vilnius University, particularly from an astronomical perspective. Its observatory, founded in 1753 and funded by Elzbieta Oginskytė, is one of Europe’s oldest, established the same year as Spain’s first in San Fernando. Lithuania installed the world’s second photoheliograph – after Kew and ahead of Harvard – laying early foundations for solar physics. As a Spaniard, I feel a connection to VU’s Jesuit heritage. Founded by Spanish students at the Sorbonne, the Jesuit order links our histories. My colleague, Dr Kazimieras Černis, has named asteroids after several Jesuit astronomers and VU rectors, including two Spaniards – Casanovas and Carreira – a small but meaningful bridge between our shared histories.

I would absolutely encourage other researchers to consider Lithuania if they’re looking for a dynamic and supportive place to live and work. It’s a peaceful and comfortable country that offers a remarkably strong environment for science and research.