VU Memory Diploma Recipient and Centenarian Vytautas Stonis: “Once My Seven Roommates Were Asleep, I Would Solve Maths Problems”

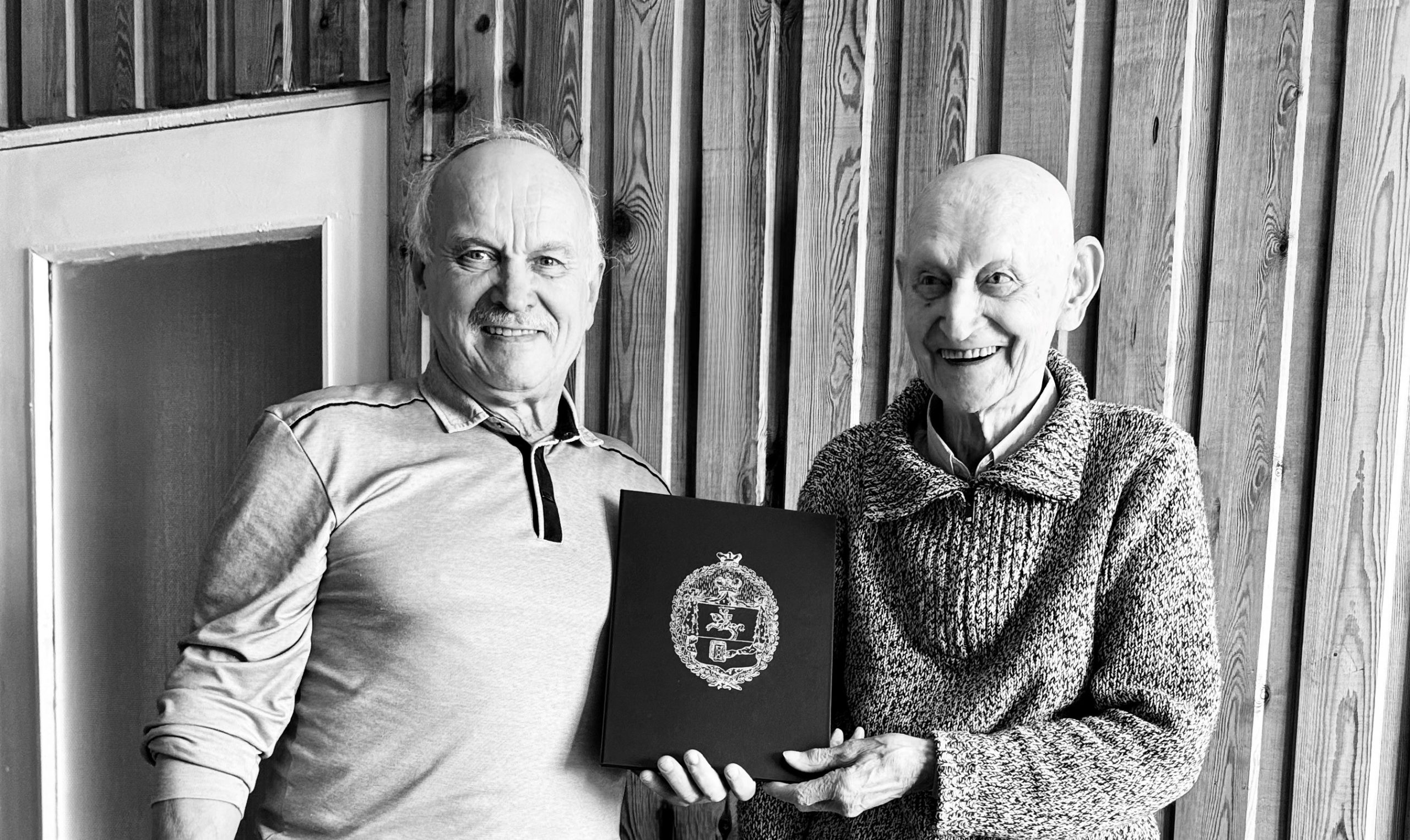

Vytautas Stonis (on the right) with a VU Memory Diploma. Photo from personal archive

Vytautas Stonis (on the right) with a VU Memory Diploma. Photo from personal archive

On 27 June, Vilnius University (VU) honoured 42 members of its community who suffered under totalitarian regimes and were expelled from the University due to historical circumstances. During a solemn ceremony, they were awarded symbolic Memory Diplomas. One of the recipients – Vytautas Stonis – is celebrating his 100th birthday this year.

Life has not been easy for him, yet the centenarian recounts his story with lightness, humour, and a touch of optimism. His academic journey was challenging from the very beginning: growing up in the countryside, Vytautas Stonis often had to switch schools to continue his education. Nevertheless, his exceptional talent for mathematics became apparent early on, so it was no wonder he was easily admitted to the VU Faculty of Economics. For the young man, the news about being accepted to the University came as both a surprise and a great joy. However, two years later, the student’s delight was overshadowed by his expulsion. As a Memory Diploma recipient, Stonis reflected on the reasons behind his dismissal, how his life unfolded afterwards, and what helped him avoid deportation.

A strict and Christian upbringing

Vytautas Stonis was born in 1925 in the village of Toliotai, in Endriejavas Rural District, Kretinga County. His parents were large-scale farmers who had inherited the land. His father served in the military for five years, fought in World War I, was taken prisoner in Germany, and was eventually released and returned home. Although Vytautas’ father had intended to give up farming, his mother persuaded him to continue.

Shortly after the young man returned home, he met his future wife. The matchmaking process, beginning the courtship, followed tradition: his father sent a neighbour to the girl to ask if she would consider marriage. She replied: “If it’s to Stonis, I’ll marry.”

Their children were raised in a strict, Christian household that valued hard work, and the parents led by example. “I remember we weren’t allowed to eat sugar, even though we had it at home. I’d take one sugar cube just so I’d have something to confess at the church, like saying I ate it without my mother’s permission. I also used to purposely skip morning and evening prayers, so I’d have a sin to confess,” he recalled with a twinkle in his eye.

A natural talent for mathematics

From 1940, Vytautas Stonis studied for two years at Švėkšna Gymnasium, then transferred to the accounting class at the Plungė School of Economics, where he studied until 1946. In his free time, he performed traditional folk dances and sang in the town choir.

Vytautas Stonis admits that he struggled with languages at school, but excelled at mathematics. However, in fifth grade, he consistently received poor grades – twos and threes – because, as he puts it, the teacher “had a thing against him”.

“One maths test stuck with me: there wasn’t a single red mark on the page, but I still got a three. Meanwhile, my classmate who sat next to me and just copied everything ended up with a five – the highest grade. The teacher told everyone who got a three to rewrite their tests and correct all the mistakes. But I didn’t know what to fix, since nothing had been marked as wrong, so I brought my notebook to her. She called me to the board, gave me a new, difficult problem, and I solved it. But she still gave me a three,” recalled the nominee.

That same teacher advised his father not to let the boy continue his education, saying he was not cut out for studies and should stay on the farm. However, his father did not believe her and allowed his son to transfer to another school instead. There, all the “learning issues” disappeared on the very first day: Vytautas Stonis did well in all subjects, never received a grade lower than a four, and never missed a single class.

When he started at Švėkšna Gymnasium, he was again among the top students. Later, he continued his studies in the accounting class of the Plungė School of Economics. Although the maths teacher there was relatively weak, it did not stop Stonis from graduating successfully and gaining admission to VU.

Solving mathematical problems in the silence of the night

After finishing the specialised economics school, the next step seemed obvious – Vytautas Stonis applied to study at the Department of Trade of the VU Faculty of Economics, and was accepted. He recalls thinking that university studies would be out of reach for him, so he was thrilled to be admitted.

“Getting into university was pure joy. I remember sitting in the auditorium for the first time, thinking: “I’m a student now”. The difference from secondary school was evident – no more dictation. Now, they gave lectures, and you had to keep up with your notes,” he said with a smile.

However, the beginning of studies brought not only joy but also serious challenges. When the young student arrived in Vilnius, he had no place to live, as he had not been assigned a dormitory room. “I didn’t know anyone in Vilnius. Those who were worse off financially were given rooms in the dormitories. I wasn’t assigned one, so I had to find a place to live. My friends from Plungė got a place in the dormitory, so they let me stay with them until the exam session. I kept going from place to place, asking people to let me stay the night. I didn’t even have proper conditions to prepare for lectures, since eight of us shared one room. I would only start solving mathematical problems once everyone else had fallen asleep,” recalled the centenarian.

Expelled without a reason

Despite these hardships, Vytautas Stonis excelled in his studies and impressed the lecturers with his sharp mind and diligence.

“I remember taking an exam with Professor Saulius Pikelis. Afterwards, he told me: ‘You’re the first student I’ve had who correctly applied multiplication and division with fractions.”

Like most young people at the time, the student enjoyed music and dancing in his free time. In the evenings, they would go dancing at discos held at the technical school, and after lectures at the University, he would perform traditional Lithuanian dances.

His joyful student life ended after two years, when he was dismissed from VU. When asked about the reason for his expulsion, he says no one ever gave him one, but he believes it was because he was “a child of a kulak” (a Soviet term for wealthier peasants who were deemed too bourgeois).

At the time, I lived in Žvėrynas near the bridge, so I stared at the river and thought: “You know where you’re flowing, but where do I go now?”

Pursuing a teaching path after expulsion

Following his dismissal, Vytautas Stonis began working as a teacher. Initially, he taught physical education, later switching to mathematics. Eventually, despite official restrictions on continuing his studies, he enrolled at the Pedagogical University to become a certified mathematics teacher. As he explains, it was a particularly difficult period: raising young children, working at school, and studying intensively: “I was learning myself and teaching my students at the same time – often just one lesson ahead of them.” His main goal as a teacher was to ensure that every student successfully completed secondary school and had the chance to get to university.

Once Vytautas Stonis began teaching, he was constantly monitored and persecuted. He recalls his last graduating class – of the cohort of 30 students, 20 joined higher education institutions, and three graduated with gold medals. ‘Still, the head of academic affairs at Žiežmariai School opposed me and my approach to education. She claimed I was encouraging the school management to defy the orders of the Education Department. Luckily, the school principal stood up for me,’ said Stonis, recalling the unpleasant incident.

Once Vytautas Stonis began teaching, he was constantly monitored and persecuted. He recalls his last graduating class – of the cohort of 30 students, 20 joined higher education institutions, and three graduated with gold medals. ‘Still, the head of academic affairs at Žiežmariai School opposed me and my approach to education. She claimed I was encouraging the school management to defy the orders of the Education Department. Luckily, the school principal stood up for me,’ said Stonis, recalling the unpleasant incident.

During his second year of teaching in Šilalė, Komsomol representatives from Tauragė visited Stonis to persuade him to join the Communist Youth League. “I refused. After a couple of hours of pressure, one of them finally said: “You should join the seminary instead.” I jumped out of my chair, opened the door, and told them to leave. That’s how I never joined the Komsomol,” he explained.

The teacher who escaped deportation

At the time, the Soviet authorities were deporting families who were educated or owned land or other property, precisely the kind of family Vytautas Stonis came from.

“I saw people leaving with full carriages. I thought, I’ll go home and check how my parents are holding up,” recalled the former teacher. On his way, he ran into a neighbour who warned him not to go home. But Vytautas Stonis ignored him and headed toward the house. He found his grandmother alone there, as his parents had gone into hiding somewhere in the woods.

As soon as he arrived, the stribai (members of the Soviet extermination battalions) broke into the house. Among them was Stonis’ former classmate. The head of the brigade began interrogating him, asking for his name and place of work. When they discovered that Stonis was a teacher and had not lived with his parents for the past seven years, they returned his documents and let him go. Back then, there was a shortage of teachers in Kuliai. “Go there and start working,” they told him.

“While I was talking with them, my brother came back from the forest. He also managed to avoid deportation that time. But the next time, at Easter, the stribai came again and deported my father, two brothers, and two sisters to Siberia,” said Vytautas Stonis, who spent his entire life working as a mathematics teacher, and this spared him from an even more tragic fate.